The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine shocked the world. It quickly resulted in an energy crisis as European countries tried to secure non-Russian energy supplies for the winter.

What followed was one of the most blatant examples of ‘shock doctrine,’ where gas operators quickly shifted their public messaging and lobbying from “energy transition” to “energy security” and cynically used the opportunity to frighten governments into massive, unneeded investment into and expansion of fossil gas imports and infrastructure. These tactics have resulted in a short-term energy supply crisis being answered by long-term fossil fuel lock-in in the form of new infrastructure, decades long contracts, and environmental impact in the US, as well as in the EU.

This overreaction jeopardises the EU’s and US’ energy transition and their agreed climate goals.

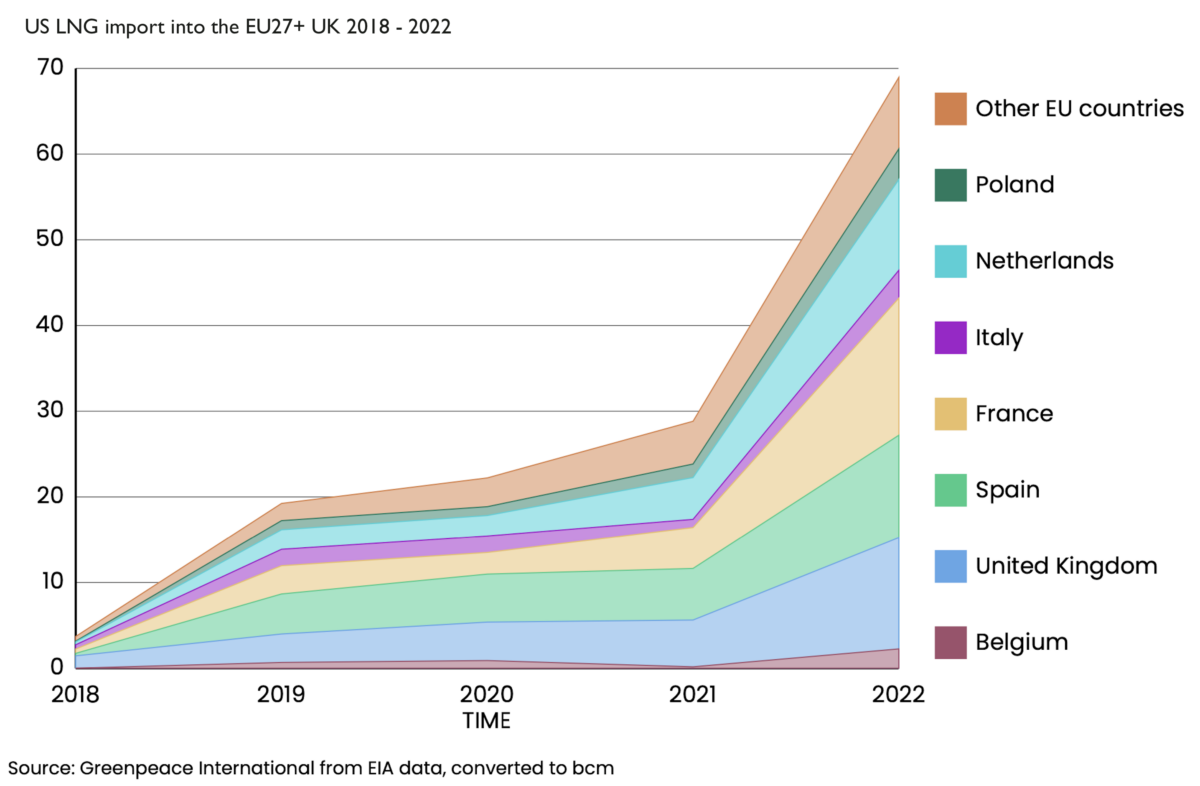

The shift was instant and effective. The REPowerEU plan, the EU answer to the gas crisis, included around €10 billion ($10.9 billion) in funding for gas infrastructure. Eight liquefied gas terminals are under construction, and 38 more have been proposed. Replacing Russian pipeline gas led to a surge of shipments of liquefied gas (also known as LNG) from the US.

As a result, gas infrastructure operators, portfolio traders, and gas companies have declared that imported liquefied gas is the answer to the crisis and will remain so for decades to come.

Shareholders of the world’s top five oil and gas companies saw record profits of €192 billion ($209 billion) and distributed $102 billion (€94 billion) in the form of dividends and share-buy-backs in 2022.

This LNG expansion threatens the health of communities living near these export terminals, extraction sites, and pipelines, while potentially pushing planet warming emissions past levels to meet global climate goals.

Why the gas is not needed

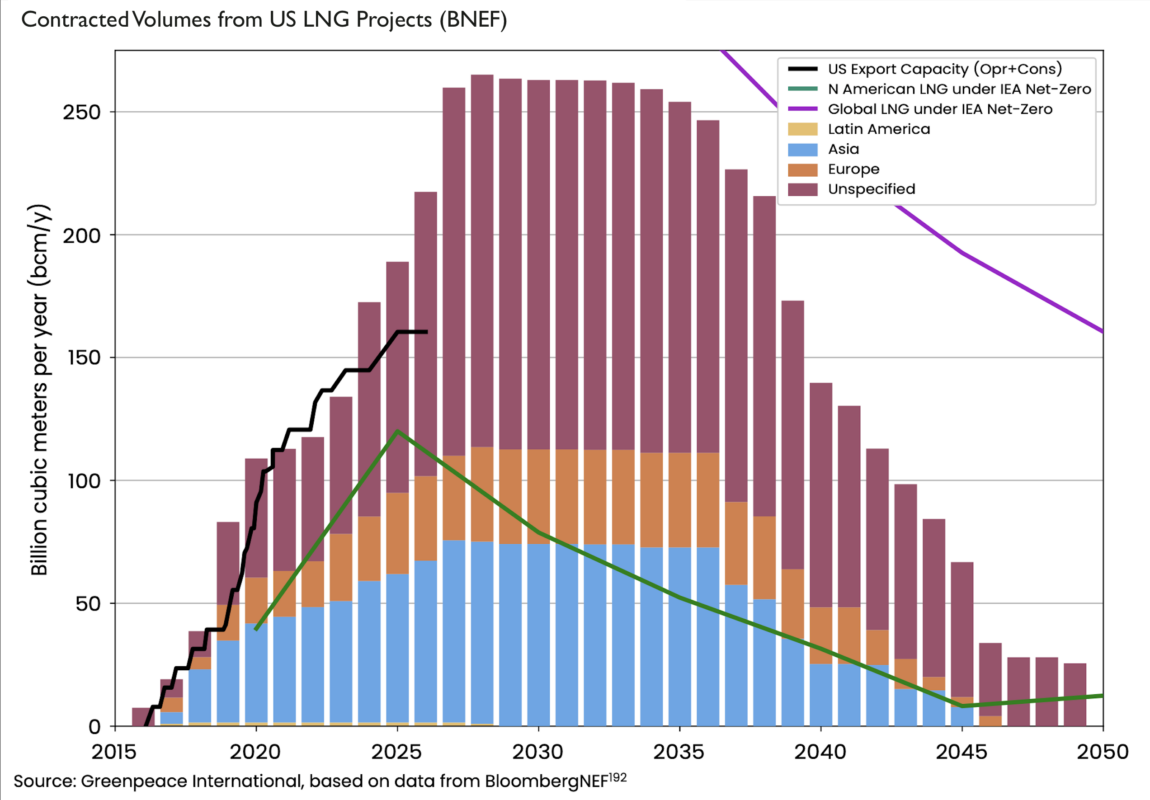

- Gas companies are capitalising on the shock of the Russian invasion of Ukraine to weaken regulations and push new proposals for increasing liquefied gas imports and locking both the US and Europe into contracts that would last for 15 to 20 years. This threatens climate goals, communities and investors.

- The reality is that most of the proposed projects would not be operational in time to address short-term energy shortages arising from the war in Ukraine. Most projects will only come online by 2026, far too late to respond to the current supply crunch.

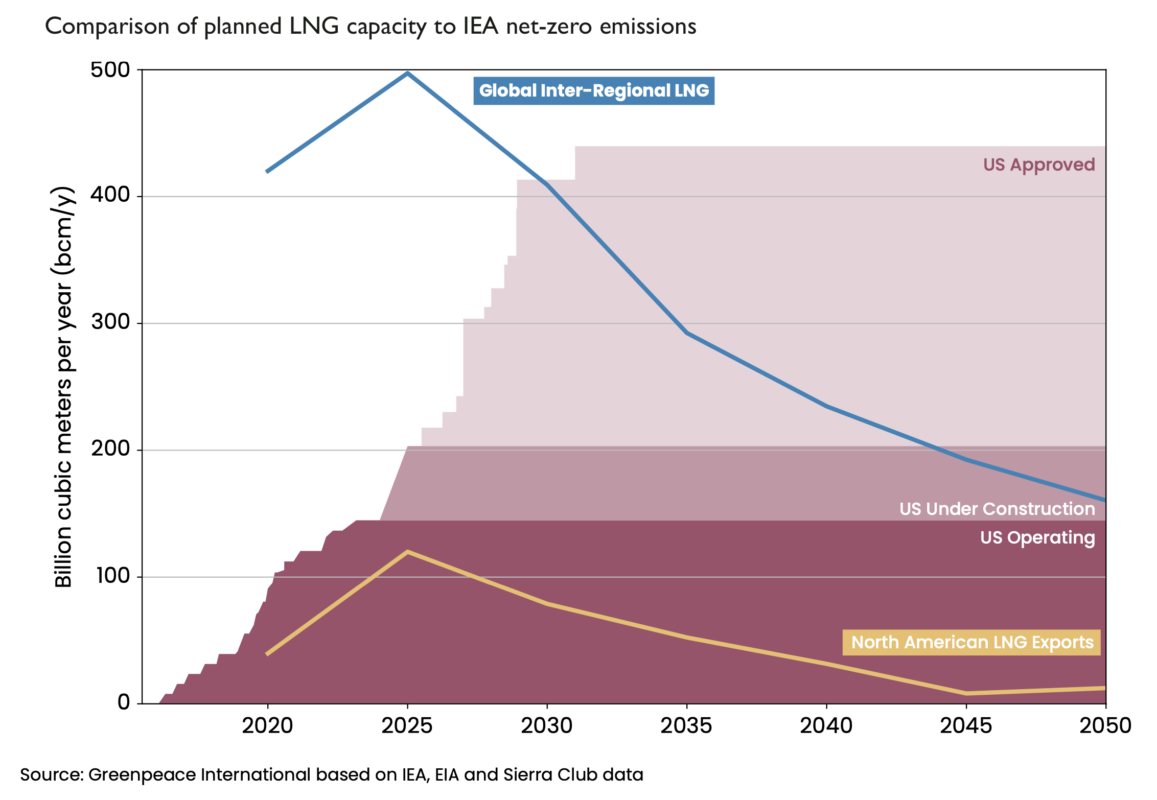

- The US has approved projects that, if built, would double liquefied gas export capacity to 439 bcm per year – with annual lifecycle emissions equivalent to 393 million cars. By 2030, US liquefied gas exports alone could exceed the Net Zero Emissions (NZE) estimate by the IEA for global liquefied gas trade.

- US liquefied gas imports to Europe increased by 140% in 2022. France accounted for nearly a quarter of these imports, with the UK and Spain following closely. At the same time plans for a raft of new import terminals are being pushed through.

- Currently in Europe eight liquefied gas terminals are under construction and 38 more have been proposed. These terminals, if built, would add 950 million tonnes of CO2-eq per year.

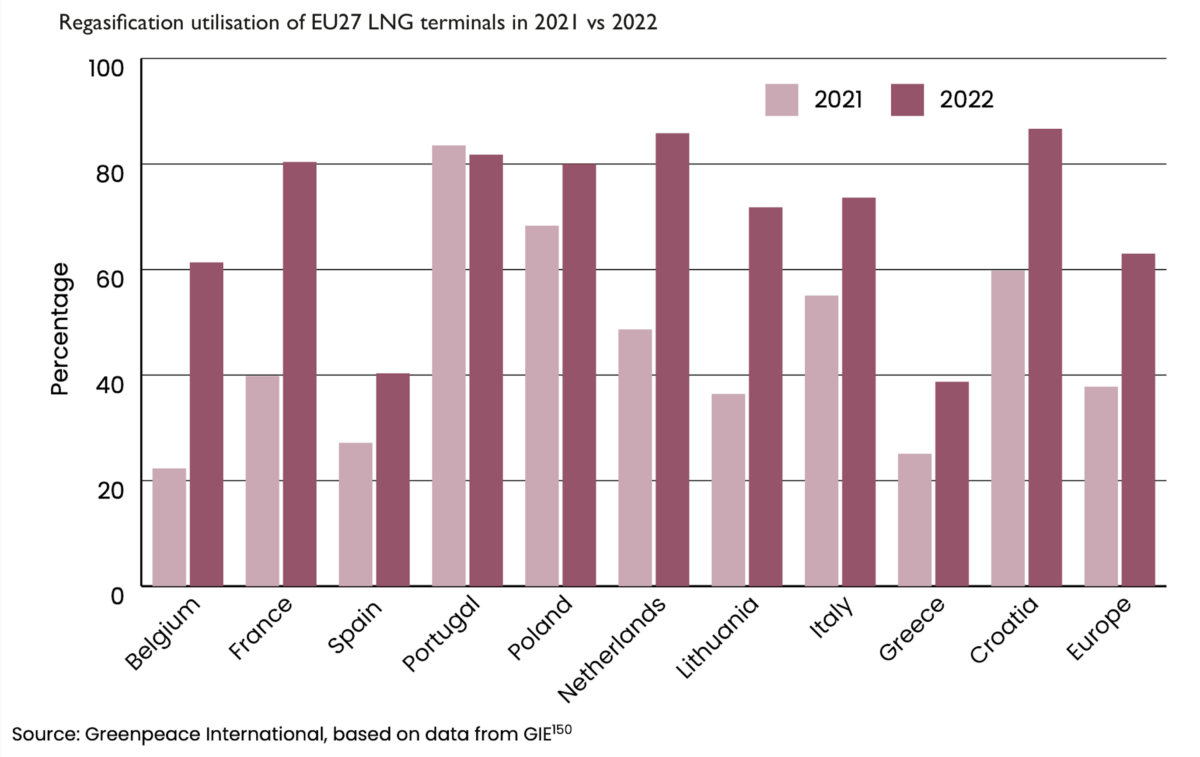

- Despite this massive surge in imports and infrastructure plans, EU liquefied gas regasification utilisation rate was only 63% in 2022.

- European climate change policies should include phasing out liquefied gas before 2030 and all fossil gas by 2035.